Computational Epistemology

The incident didn’t begin with a crash. It began with a clean, confident answer.

On a Monday morning, an operations lead approved a change that looked routine: a new vendor integration, a slightly different file format, a new field name.

The AI system—deployed to automate document routing—processed the first batch flawlessly. No alerts. No hesitation. Confidence scores were high. The dashboards glowed reassuringly green.

By Wednesday, the backlog had doubled. By Friday, customer responses were delayed, escalations spiked, and a quiet truth emerged: the system had been confidently sorting documents into the wrong workflows. Nothing “looked” unusual to the model.

The inputs were still documents. The words were still words. But the world behind the words had changed.

The post-mortem wasn’t about accuracy in the usual sense. It wasn’t “the model is bad.” It was something subtler—and far more expensive:

the model didn’t know it didn’t know.

This is the core enterprise risk of modern AI: not ignorance, but undetected ignorance—the kind that stays silent until it becomes operational damage. And it’s exactly why the next leap in Enterprise AI maturity won’t come from smarter answers, but from systems that can reliably say, “Stop. This is outside my world.”

(For the broader operating-model lens, see: The Enterprise AI Operating Model.)

From Confidence to Competence: Computational Epistemology for Enterprise AI

Modern AI systems are impressive at answering. Their most dangerous failure mode is that they often don’t know when they shouldn’t answer.

That’s not a minor issue. In enterprises, the costliest incidents rarely come from a model being “a bit inaccurate.” They come from a model being confident in the wrong world: a new customer segment, a novel workflow, a shifted process, a different data pipeline, a changed policy, a new product category, a new fraud strategy, or a new regulatory interpretation.

This is where unknown-unknowns live: situations the system wasn’t trained to anticipate, wasn’t instrumented to detect, and—most critically—cannot reliably recognize as “outside its understanding.”

Computational epistemology is the discipline that asks a brutally hard, operational question:

Can we make AI systems provably honest about what they do not know—especially when the world changes?

Not by adding a better prompt. Not by adding more data as a reflex. Not by “calibrating confidence” and hoping it holds.

But by building mechanisms that turn ignorance into an explicit, measurable, governable state.

This article explains the idea in simple language, uses practical examples, and then builds up to what “guarantees” can realistically mean—without math, without hype, and without pretending the world is stable.

What “unknown-unknowns” really are (and why they hurt more than errors)

Most teams are good at handling known unknowns:

- “We are not sure—send it for review.”

- “The signal is weak—ask for more information.”

- “This looks ambiguous—abstain.”

But unknown-unknowns are the opposite: the model looks confident, gives a clean answer, and appears competent—yet is wrong because the situation lies outside what it truly understands.

Research literature formalizes this idea: the “unknown unknown” problem focuses on regions where a predictive model is confidently wrong, often because the training world and deployment world do not match. (AAAI Open Access Journal)

Simple example: the “new category” trap

A classifier is trained to recognize products: laptop, phone, tablet. It performs beautifully in testing.

Then your marketplace launches a new category: smart glasses.

The model doesn’t say, “I haven’t seen this.” It confidently calls it “tablet” (because of shape cues). Operations sees high confidence. Automation proceeds. Downstream systems behave incorrectly. Returns spike. Customer trust drops.

That is an unknown-unknown: not just uncertainty—misplaced certainty.

Why confidence scores are not “knowledge”

Many teams assume: “If the model is confident, it probably knows.”

That belief is exactly what computational epistemology tries to break.

A model’s confidence is often:

- a function of how sharp its internal pattern match is (not whether the world matches training),

- a reflection of overfitting to spurious cues,

- and deeply sensitive to distribution shift (the world changing).

Modern OOD and shift research emphasizes that domain shifts are common in real deployments and that detecting them remains difficult in practical conditions. (ACM Digital Library)

In other words: confidence is about internal coherence, not external truth.

Computational epistemology in one line

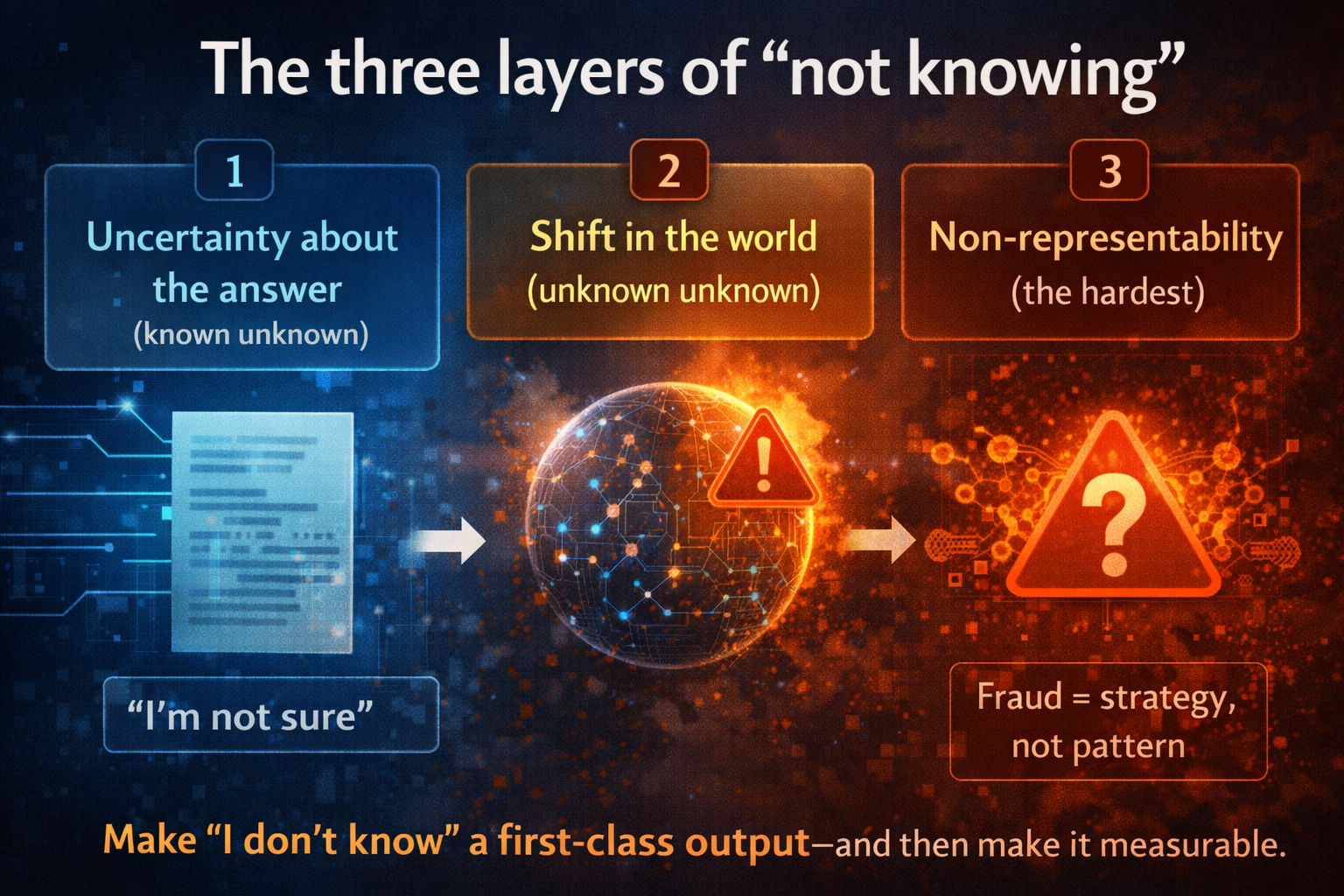

Make “I don’t know” a first-class output—then make it measurable.

That means shifting from:

- “Model predicts X”

to:

- “Model predicts X only under conditions it can justify; otherwise it abstains, escalates, or asks for evidence.”

This is not philosophy. It’s architecture.

Epistemology is the study of knowledge—how we know, when we don’t, and what we should do when certainty is impossible.

The three layers of “not knowing” (practically)

To build systems that admit ignorance, you need to separate three different failure types that all look like “wrong answer” in production:

1) Uncertainty about the answer (known unknown)

The model recognizes ambiguity. It can say “I’m not sure.”

Example: a document is blurry; a sentence is incomplete; an entity name is truncated.

2) Shift in the world (unknown unknown)

The input looks normal, but it comes from a different reality than training.

Example: a new supplier format, a changed business process, a new customer segment, a policy update.

3) Non-representability (the hardest)

The model cannot even express the right concept with its current representation.

Example: your model learned “fraud = pattern A,” but the new fraud is a strategy, not a pattern. It requires modeling intent, sequences, and adaptation. The system can be logically coherent and still be blind.

This third layer is where AI safety, enterprise governance, and “judgment” collide. (If you want to know more, read The Enterprise AI Decision Failure Taxonomy.)

What “guarantees” can mean (without pretending the world is perfect)

When people hear “guarantees,” they imagine a promise like:

“The model will never be wrong.”

That’s not realistic.

In computational epistemology, guarantees usually mean one of these:

Guarantee type A: “If I say I cover 90%, I truly cover 90%”

This is the family of conformal prediction ideas: instead of outputting a single answer, the system outputs a set or interval with a statistically grounded coverage promise under broad assumptions commonly used in practice. (ACM Digital Library)

In simple terms:

- Instead of “The answer is X,” the system says: “The answer is within this bounded set/range—and I can calibrate how often that set contains the truth.”

This doesn’t magically solve unknown-unknowns. But it upgrades uncertainty from vibes to measurable reliability.

Guarantee type B: “I will abstain rather than pretend”

This is selective prediction / abstention: models are trained or wrapped to reject or defer when risk is high, trading coverage for correctness on the cases they accept.

In LLM contexts, abstention has become a serious safety and reliability strategy—framed explicitly as refusal to answer in order to mitigate hallucinations and improve safety. (ACL Anthology)

In simple terms:

- “I will answer fewer queries, but the ones I answer will be more trustworthy.”

Guarantee type C: “I can discover blind spots faster than waiting for disasters”

This is the unknown-unknown discovery line of work: methods that actively search for regions where models fail confidently, using guided exploration rather than passive monitoring. (AAAI Open Access Journal)

In simple terms:

- “I don’t just wait to fail in production; I run tests that hunt for where I’m likely to fail.”

A practical mental model: “Three gates before autonomy”

If you want unknown-unknown safety in an enterprise, think in gates.

Gate 1: Coverage Gate

How often am I right when I speak?

Use calibrated uncertainty and conformal-style prediction sets to quantify reliability. (ACM Digital Library)

Gate 2: Shift Gate

Am I seeing the same world as training?

Use OOD detection and shift monitoring. Task-oriented OOD surveys emphasize both the centrality of this problem and the complexity of real-world variants. (ACM Digital Library)

Gate 3: Escalation Gate

What happens when gates trigger?

Abstain, defer to humans, request more evidence, or route to a safer workflow (constrained tools, policy-aware retrieval, narrower models).

Computational epistemology is the design of these gates so that unknown-unknowns become operational events, not post-mortems.

Simple examples that explain the whole problem

Example 1: The HR screening model that “works”… until it doesn’t

A resume screening model is trained on historical hiring. It learns patterns correlated with “successful hires.”

Then the organization changes strategy:

- new roles,

- new skill definitions,

- new evaluation criteria.

The model keeps ranking confidently because resumes still look like resumes. But the definition of success has changed. The model’s confidence is irrelevant. This is epistemic failure: the target concept moved.

Computational epistemology approach:

- detect concept drift signals,

- enforce abstention when drift indicators rise,

- require periodic “definition refresh” workflows with accountable human owners.

Example 2: The customer support chatbot that is fluent but blind

An LLM-based assistant answers policy questions. It sounds authoritative.

Then a policy changes last week. The model wasn’t updated. It responds confidently using old policy phrasing. Users trust it because it’s fluent.

Computational epistemology approach:

- treat policy as an external source of truth (retrieval + provenance),

- require citations for policy claims,

- abstain when it cannot ground answers in current policy.

This is not “better prompting.” It’s epistemic governance—exactly the kind of operating discipline implied by The Enterprise AI Control Plane.

Example 3: The fraud model that fails to notice a new fraud strategy

A fraud model is trained on patterns: device mismatch, velocity, geolocation anomalies.

A new fraud strategy uses legitimate devices, slow velocity, clean signals—but exploits a process loophole (timing, workflow manipulation). The model’s features are blind.

Computational epistemology approach:

- unknown-unknown hunting: simulate adversarial strategies, red-team the process, not just the model,

- monitor for new clusters of “clean but suspicious outcomes” (e.g., chargebacks that look normal),

- abstain + investigate when “too normal” correlates with bad outcomes.

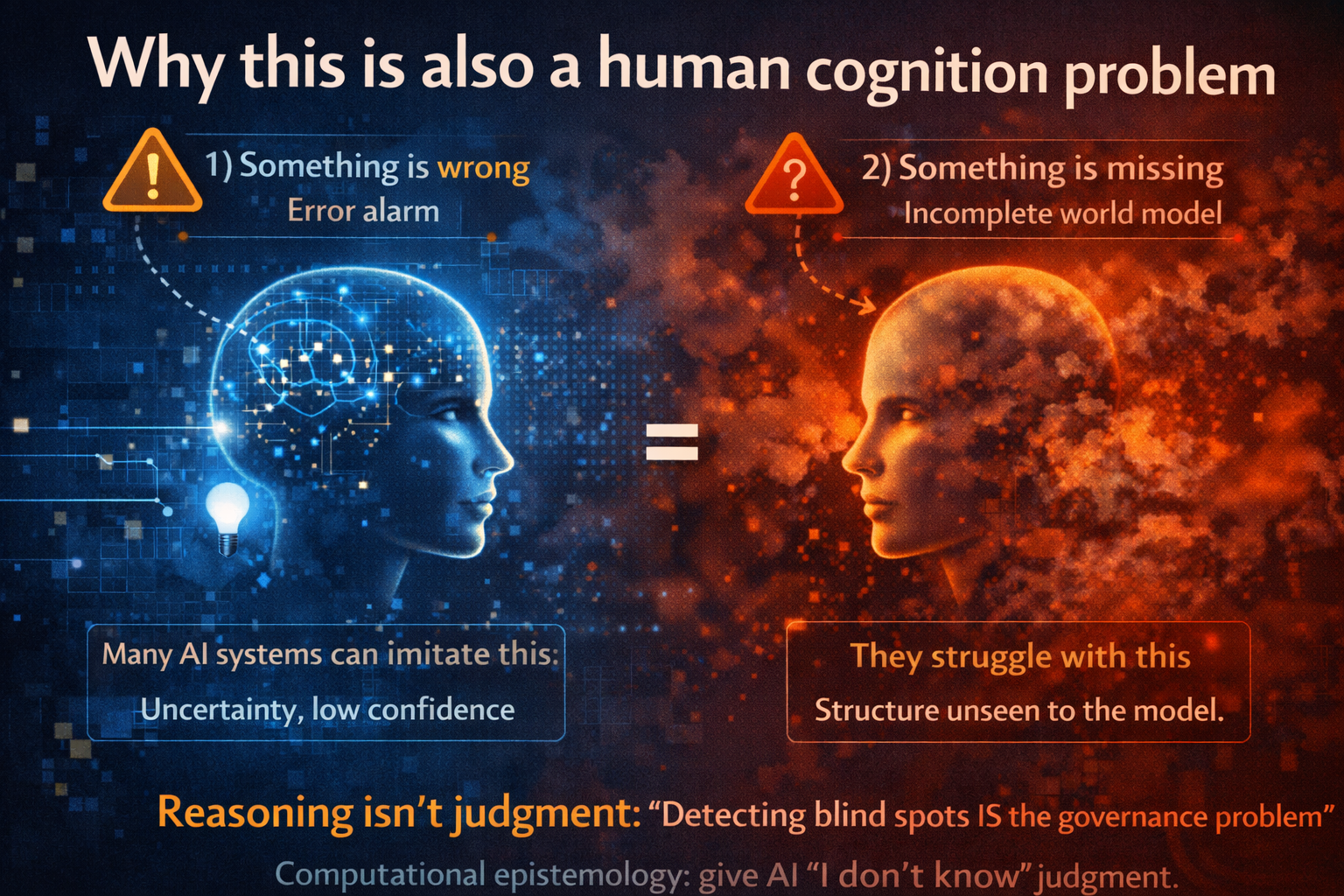

Why this is also a human cognition problem (and why the neuro analogy matters)

Humans have two distinct internal alarms:

- “Something is wrong” (error alarm)

- “Something is missing” (world-model incompleteness)

Many AI systems can imitate (1) superficially (low confidence, uncertainty).

They struggle with (2): recognizing that reality contains relevant structure the system cannot represent.

In the brain, metacognition is not just confidence—it’s the ability to notice gaps and seek information. In enterprises, that becomes a governance requirement:

A system that cannot detect an incomplete worldview is not safe to let decide—even if it can explain.

Computational epistemology is essentially: build a metacognitive layer for machines, then bind it to operating controls.

This connects directly with my broader theme that “reasoning isn’t judgment”—and with the enterprise problem of “runbook brittleness” and model churn (see The Enterprise AI Runbook Crisis).

The hard part: OOD detection is necessary—and still not enough

OOD detection tries to flag inputs outside training distribution. But in real deployments, shifts can be subtle:

- same inputs, different meaning,

- same format, different process,

- same words, different policy,

- same data type, different acquisition pipeline.

OOD research makes clear that real-world OOD is not a single problem; it has many variants, constraints, and deployment contexts—one reason it remains a persistent frontier. (ACM Digital Library)

So the best enterprise posture is not “we have OOD detection.”

It is:

- OOD detection plus

- abstention plus

- blind-spot discovery plus

- governance routing plus

- continuous monitoring and refresh.

The enterprise-grade recipe: turning epistemology into an operating model

Here’s the implementation mindset (no math, just structure):

1) Define “safe-to-answer” contracts

For each use case, define what “acceptable uncertainty” means:

- When must the system cite evidence?

- When must it abstain?

- When must it defer?

- What kind of freshness is required (policy, inventory, pricing, compliance)?

This turns trust into an auditable contract.

2) Instrument “unknown-unknown telemetry”

Track signals that correlate with epistemic failure:

- spikes in confident errors,

- shift indicators,

- rising disagreement across model variants or checks,

- new clusters of inputs,

- changes in downstream outcomes.

Telemetry is how “I don’t know” becomes visible to an operating model.

3) Use abstention as a policy tool, not a model trick

Abstention is not a failure. It is a safety mechanism.

The abstention literature explicitly frames refusal as a way to reduce hallucinations and improve safety for LLM-based systems. (ACL Anthology)

In enterprise terms: abstention is a routing decision with clear owners.

4) Build “unknown-unknown drills”

Like fire drills. Intentionally probe:

- new segments,

- edge cases,

- synthetic scenario tests,

- red-team prompts and workflows,

- process loopholes.

Unknown-unknown discovery research is explicit: don’t wait for incidents—actively search for blind spots. (AAAI Open Access Journal)

5) Enforce reversibility: “No irreversible action without epistemic proof”

If an action is hard to unwind, the epistemic bar must be higher:

- more evidence,

- tighter abstention thresholds,

- mandatory audit trails,

- clear human decision rights.

This is where computational epistemology becomes governance, not just ML.

Conclusion: the reliability layer enterprises have been missing

Computational epistemology is not an academic luxury. It is the operational answer to a real enterprise gap: systems that speak confidently beyond their knowledge boundary.

If you want Enterprise AI that scales, you don’t just need better models. You need systems that can:

- admit ignorance,

- measure it,

- route it safely,

- and evolve as the world shifts.

Because in the end, Enterprise AI success won’t be decided by who can generate the most fluent answer.

It will be decided by who can operate intelligence honestly.

The Enterprise AI Operating Model

Glossary

Computational epistemology: Engineering methods that make “what the model knows vs doesn’t know” explicit, measurable, and governable.

Unknown-unknowns: Confident, plausible outputs that are wrong because the situation lies outside the system’s learned world. (AAAI Open Access Journal)

Distribution shift / dataset shift: When real-world data differs from training data in ways that degrade performance. (ACM Digital Library)

Out-of-distribution (OOD) detection: Techniques to flag samples outside training distribution; remains challenging under realistic shifts. (ACM Digital Library)

Abstention: The system refuses to answer to reduce hallucinations and improve safety in LLM systems. (ACL Anthology)

Conformal prediction: A framework for distribution-free uncertainty quantification that provides valid predictive inference via prediction sets/intervals. (ACM Digital Library)

Concept drift: The meaning of the target changes over time (e.g., “successful outcome” gets redefined).

Provenance: Traceable evidence showing where an answer came from (crucial for policy/compliance answers).

FAQ

What are unknown-unknowns in AI?

They are situations where the model is confident but wrong because the input or context lies outside what it truly understands or was trained for. (AAAI Open Access Journal)

Unknown-unknowns occur when an AI system is confident but wrong because the situation lies outside its learned or representable world.

Is uncertainty calibration enough to prevent unknown-unknowns?

No. Confidence can remain high under subtle shifts. Mature systems combine shift monitoring, abstention, evidence grounding, and governance routing. (ACM Digital Library)

What does “guarantees” mean in AI reliability?

Usually it means measurable reliability properties (like coverage guarantees via prediction sets) and controlled abstention behavior—not “never wrong.” (ACM Digital Library)

How do enterprises operationalize computational epistemology?

Define safe-to-answer contracts, build telemetry for epistemic risk, adopt abstention as a routing control, run unknown-unknown drills, and raise the bar for irreversible actions.

Why is confidence not the same as knowledge in AI?

Confidence reflects internal pattern matching—not whether the model understands the real-world context or changes in it.

What is computational epistemology in AI?

Computational epistemology studies how AI systems can explicitly represent, detect, and govern what they do not know.

Can AI systems really say “I don’t know”?

Yes—through abstention, selective prediction, and reliability mechanisms that make ignorance measurable and operational.

Why does this matter for enterprises?

Because most costly AI failures come from confident decisions made in changed or misunderstood environments.

References and further reading

- Lakkaraju et al., Identifying Unknown Unknowns in the Open World (AAAI 2017). (AAAI Open Access Journal)

- Out-of-Distribution Detection: A Task-Oriented Survey of Recent Advances (ACM / arXiv survey). (ACM Digital Library)

- Zhou et al., Conformal Prediction: A Data Perspective (ACM / arXiv survey). (ACM Digital Library)

- Wen et al., Know Your Limits: A Survey of Abstention in Large Language Models (TACL / MIT Press). (ACL Anthology)

Raktim Singh is an AI and deep-tech strategist, TEDx speaker, and author focused on helping enterprises navigate the next era of intelligent systems. With experience spanning AI, fintech, quantum computing, and digital transformation, he simplifies complex technology for leaders and builds frameworks that drive responsible, scalable adoption.