The Completeness Problem in Mechanistic Interpretability

Mechanistic interpretability made a promise that felt refreshingly ambitious in an era of opaque machine learning: not merely to predict what an AI system will do, but to explain how it does it—inside the model itself.

In recent years, that promise has begun to look credible. Researchers have traced circuits, isolated features, and uncovered internal pathways that appear to correspond to real computations.

Yet as frontier models grow larger, more capable, and more entangled, an uncomfortable question is emerging beneath this progress: even in principle, can mechanistic interpretability ever be complete?

That is, can every meaningful model behavior be explained in a way that is both causally faithful and genuinely usable by humans—or are some behaviors destined to remain structurally resistant to human-scale explanation, not because we lack better tools, but because of how high-capacity models represent and combine information?

The completeness problem in mechanistic interpretability refers to the possibility that some AI model behaviors cannot be fully explained in a way that is simultaneously faithful, compact, stable, and human-usable—due to superposition, underspecification, and causal entanglement in frontier models.

The promise that made interpretability famous—and the question that could break it

Mechanistic interpretability made a bold promise to the AI world:

Not merely “I can predict what the model will do,” but “I can show you how it does it—inside the model.”

That promise has started to look real. We’ve seen credible maps of circuits, activation patching that identifies causal paths, and scalable feature discovery methods that begin to “unmix” internal representations. The field is no longer just commentary; it is increasingly experimental and intervention-based. (arXiv)

But success creates a sharper question—one that serious teams now have to face:

Can mechanistic interpretability ever be complete?

By “complete,” I don’t mean “we have a lot of insights” or “we explained a few behaviors.”

I mean something stronger:

Can we always produce an explanation that is faithful to the model and usable by humans—even as models scale, evolve, and get deployed into messy real-world systems?

That question is the completeness problem.

And the uncomfortable possibility is this:

Some behaviors may be fundamentally unexplainable in a human-usable way—not because we lacked effort, but because of how high-capacity models represent information.

Mechanistic interpretability does not fail because we lack tools—but because some representations resist human-scale abstraction.

This article is a careful argument for why that might be true—without math, without mysticism, and with examples you can recognize.

What “complete interpretability” would actually mean

The word “interpretability” is overloaded. So let’s define the standard we’re discussing.

A mechanistic explanation is complete if it is:

- Faithful — it tracks the real causal story inside the model (not a plausible narrative).

- Sufficient — it accounts for the behavior across a meaningful range of inputs, not a curated demo.

- Compact — it is small enough to be understood, audited, and acted upon.

- Stable — it remains valid across fine-tuning, updates, and distribution shift (or at least degrades predictably).

Much of modern mechanistic interpretability is explicitly aiming at faithfulness by using causal interventions rather than just visualizations. The causal abstraction line of work is one clear attempt to put this on firm footing. (arXiv)

But completeness is harder than faithfulness.

Faithfulness asks: “Is your explanation real?”

Completeness asks: “Does a usable explanation always exist?”

That’s where the cracks show up.

A warm-up analogy: the transparent engine illusion

Imagine someone gives you a transparent engine. You can watch every gear turn.

Does that make the engine “explainable”?

Not necessarily.

Because “seeing everything” doesn’t automatically give you:

- the right abstraction level,

- the right causal decomposition,

- or a concise story of what matters.

Frontier AI models are far worse than engines: they are distributed, high-dimensional, and compressive. Even if you can observe internals, the structure you see may not compress into a human-auditable explanation.

In practice, completeness gets blocked by four structural obstacles:

- Superposition — many features are packed into shared internal space

- Non-robust features — predictive cues can be real but alien to human concepts

- Underspecification — multiple different internal “solutions” can behave the same externally

- Causal entanglement — behavior arises from overlapping pathways that resist clean decomposition

Let’s unpack each—carefully.

1) Superposition: when the model stores many ideas in the same place

One of the most important modern insights is superposition: models can represent more features than they have obvious “slots” (neurons, dimensions) by packing them into shared space, at the cost of interference. (arXiv)

A simple example:

Picture a crowded room with many conversations. You place a few microphones around the room. Each microphone records mixtures of voices.

You can still recover meaning—sometimes impressively—

but no microphone corresponds to one clean speaker.

That’s superposition.

In neural networks, this shows up as:

- polysemanticity (units participate in multiple unrelated “concepts”),

- feature overlap,

- interference patterns that vary with context. (arXiv)

Why superposition creates a completeness barrier

If you want to “fully explain” a behavior, you want a clean story like:

“These are the relevant features, and here is how they combine into the output.”

But with superposition, important features may be:

- not cleanly separable,

- not aligned to human concepts,

- and not stable across contexts.

So “complete explanation” starts to resemble an impossible task: producing a definitive transcript of every overlapping conversation from a set of mixed recordings.

Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) and related techniques are a major step forward because they can partially de-superpose activations into more interpretable features at scale. (Anthropic)

But even here, a hard question remains:

Are we recovering the model’s true “atoms of computation”—or merely finding one convenient coordinate system that looks clean?

That question flows directly into underspecification. But first, another limit.

2) Non-robust features: the model may be right for reasons humans can’t recognize

A second structural obstacle comes from robustness research: the idea that models exploit non-robust features—patterns that are genuinely predictive, yet brittle and often incomprehensible to humans. (arXiv)

A simple example:

Imagine an inspector who can detect microscopic manufacturing signatures correlated with failure. Those signatures are real and predictive—but invisible to normal human inspection.

Now imagine you demand: “Explain your decision using only human-visible concepts.”

The inspector may be correct, yet unable to translate the cause into your vocabulary.

That’s what non-robust features imply for interpretability:

- The model may rely on real predictive cues,

- that don’t map cleanly to human concepts,

- and that can be disrupted by tiny, irrelevant changes. (arXiv)

Why this threatens completeness

Mechanistic interpretability often assumes there exists a “human-readable algorithm” inside the model.

But if performance depends on high-dimensional cues that aren’t concept-aligned, then the most faithful explanation may be:

“It used a pattern that is real and predictive, but not representable in your concept vocabulary.”

That’s not satisfying.

But it may be the correct kind of answer.

In other words: some behaviors may be explainable only in a language humans don’t naturally speak.

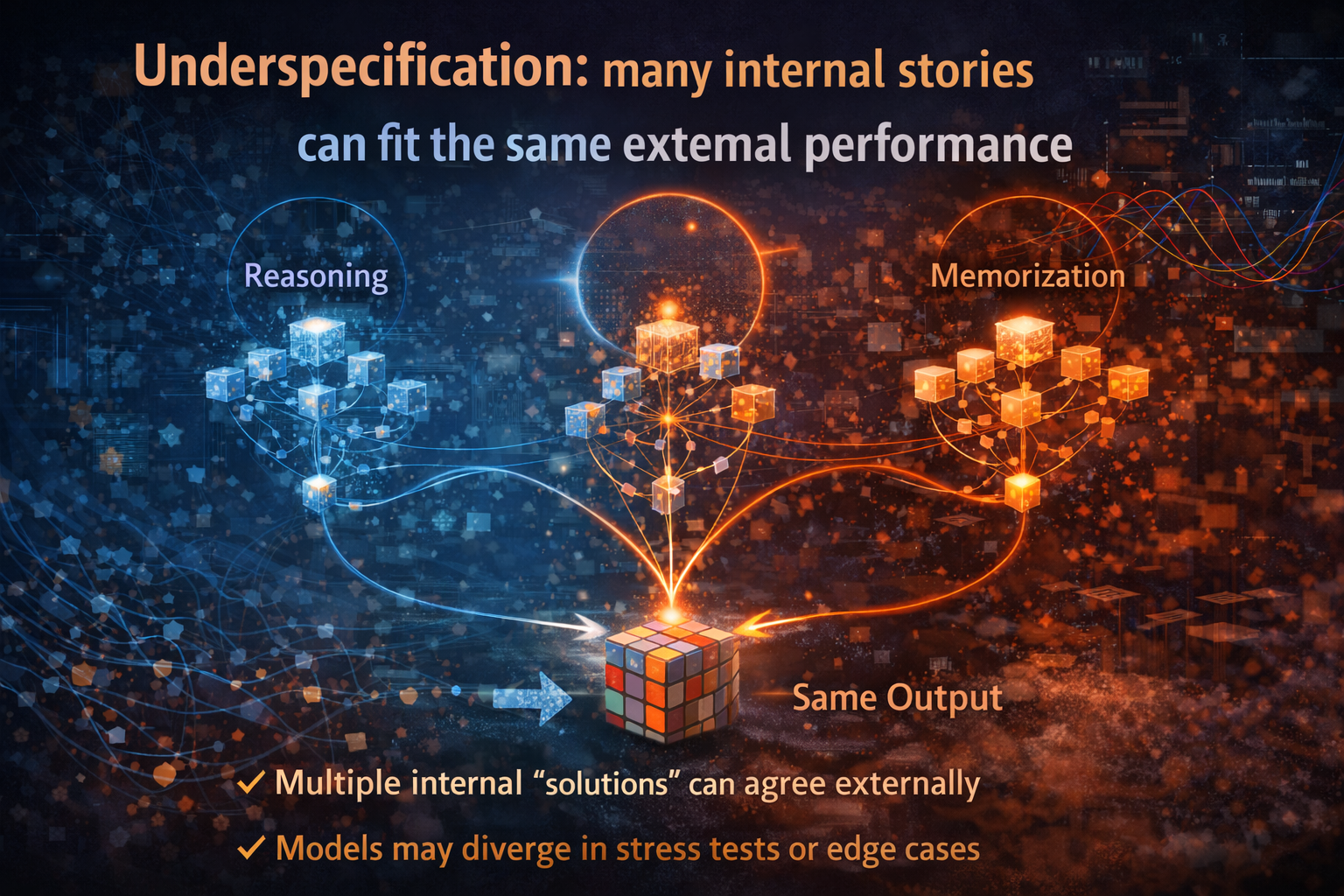

3) Underspecification: many internal stories can fit the same external performance

The third obstacle is underspecification: modern ML pipelines can produce many distinct predictors that look equally good on test metrics—yet behave very differently under real-world conditions. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

In plain language:

The same external behavior can be implemented by different internal mechanisms.

A simple example:

Two people give the same answer.

- One reasoned it out.

- The other memorized it.

Externally: identical.

Internally: fundamentally different.

Underspecification means:

- there may not be a single “true” mechanism to discover,

- because training could have landed on many internal solutions that all satisfy the same validation criteria. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

Why underspecification breaks the dream of “the one correct explanation”

Even if you reverse-engineer a faithful mechanism for this model, the next training run (or fine-tune) may implement the same behavior differently while preserving benchmark performance.

That makes interpretability fragile as a completeness claim.

It also explains why mechanistic interpretability is increasingly paired with causal testing: it’s not enough to have a story; you must verify that the story is causally anchored. (arXiv)

But completeness would require more: explanations robust across the underspecified space of equally-valid models.

That is an unusually high bar.

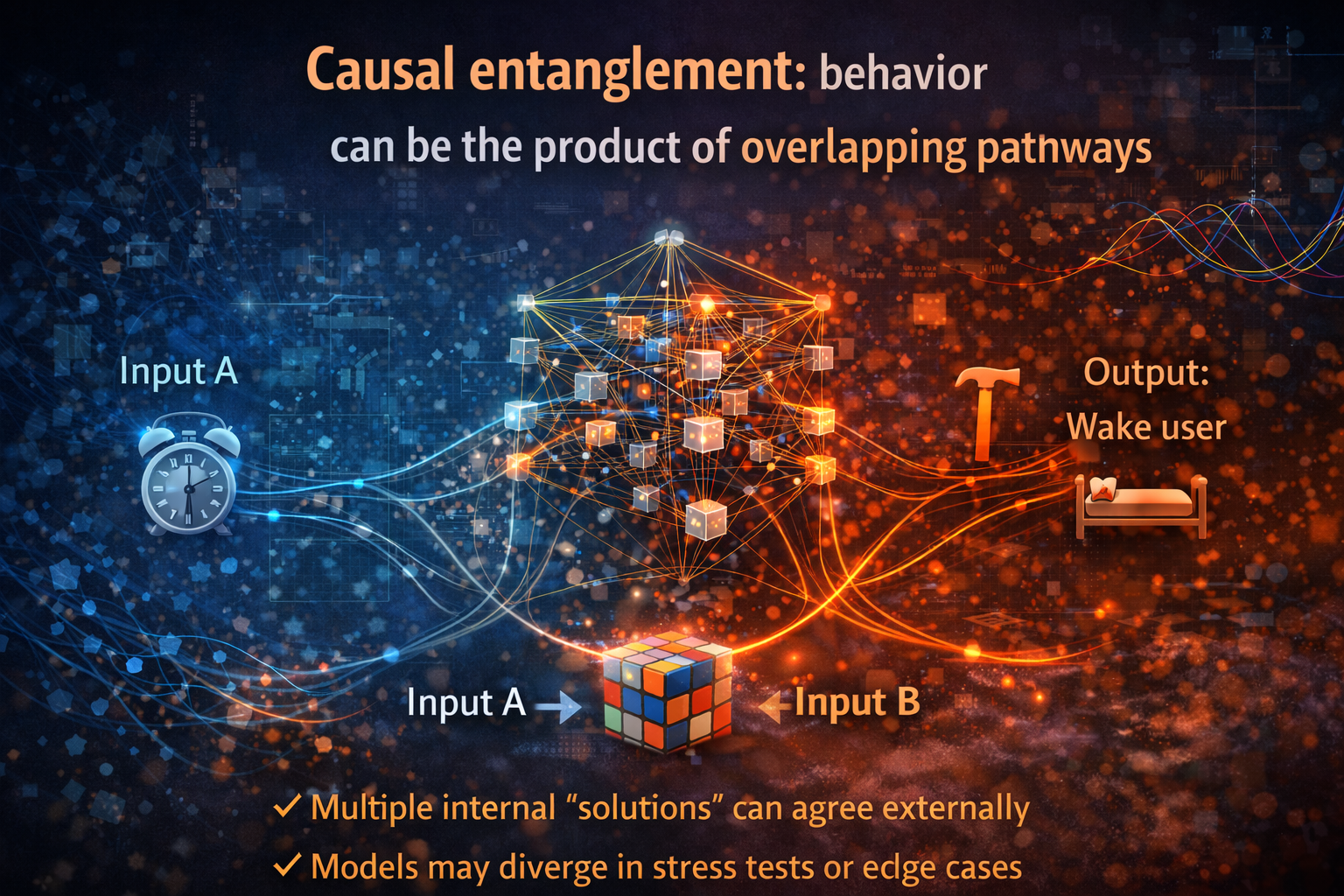

4) Causal entanglement: behavior can be the product of overlapping pathways

The final obstacle is subtle but common: causal entanglement.

Even when we identify a “circuit,” it may not be:

- minimal,

- unique,

- or separable.

Frontier models frequently implement behaviors through distributed coalitions:

- many attention heads contribute partially,

- many layers provide redundant routes,

- the final output is an aggregate of overlapping influences.

This is why the field increasingly frames interpretability around interventions and graded faithfulness—rather than purely descriptive interpretations. (arXiv)

Why this threatens completeness

A complete explanation would ideally let you say:

- “These are the causal parts.”

- “These are irrelevant.”

- “This is the mechanism.”

But in high-dimensional systems, you may have:

- many causally relevant contributors,

- none individually decisive,

- and enough redundancy that “the mechanism” is not a single compact object.

At that point, explanation becomes less like a recipe and more like weather: many interacting factors, partial predictability, and sensitivity to context.

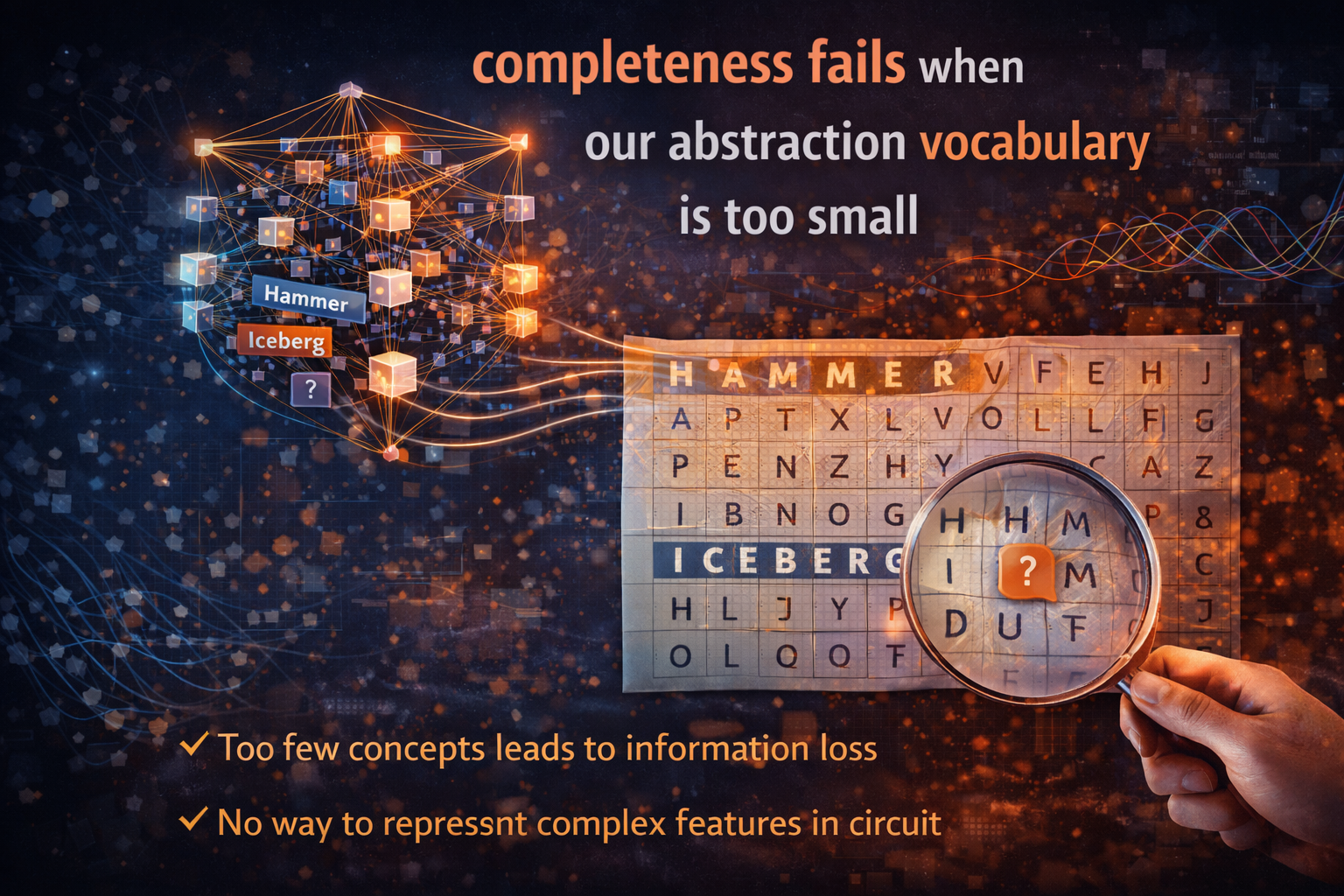

The core insight: completeness fails when our abstraction vocabulary is too small

Here is the thesis in one line:

Interpretability is not only about finding mechanisms. It is about finding mechanisms that fit inside a usable abstraction language.

Superposition says concepts overlap. (arXiv)

Non-robust features say models can be right in alien ways. (arXiv)

Underspecification says multiple internal stories can fit the same outputs. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

Causal entanglement says behavior may resist clean decomposition. (arXiv)

So the completeness problem is not “we need a better microscope.”

It is: even with a microscope, what you see may not compress into a human-auditable story.

The goal of interpretability is shifting from “explain everything” to “extract enough causal structure to govern safely.”

What mechanistic interpretability can still promise—and what it should stop promising

This is not pessimism. It’s precision.

What interpretability can promise

-

Local mechanisms for bounded behaviors

You can often get strong mechanistic accounts for specific capabilities, tasks, or failure modes—especially when paired with interventions. (arXiv)

-

Causal tests for whether an explanation is real

Causal abstraction frameworks explicitly aim to move interpretability from “plausible narrative” to “tested simplification.” (arXiv)

-

Scalable feature discovery

De-superposition methods like SAEs can produce usable features at scale, even if they do not guarantee uniqueness or completeness. (Anthropic)

-

Practical safety and governance wins

Even incomplete interpretability can surface brittle heuristics, unsafe triggers, and unexpected internal dependencies—especially when integrated into monitoring and decision governance.

What interpretability should stop promising

- Global, complete explanations for all frontier behaviors

Not impossible in every case—but too risky as a default assumption. - One “true” mechanism for a capability

Underspecification makes uniqueness fragile. (Journal of Machine Learning Research) - Human-concept alignment as a guaranteed end state

Non-robust features show “alien competence” can be real competence. (arXiv)

A practical Completeness Checklist for serious teams

When someone claims: “We’ve explained the model,” ask:

- Faithfulness: Was the explanation tested via interventions, or inferred via visualization alone? (arXiv)

- Scope: Does it hold across diverse inputs, or only handpicked cases?

- Uniqueness: Are there alternative mechanisms that fit equally well? (underspecification) (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

- Stability: Does it survive fine-tuning, updates, or distribution shift?

- Abstraction fit: Is the explanation actually usable for governance, audit, safety gating, or debugging?

If 1–3 are weak, you may have a narrative—not a mechanism.

Why this matters for enterprise AI governance

The completeness problem is not academic. It changes how you should govern AI.

- Auditability: Regulators often want “the reason.” But some reasons may not compress into policy-friendly categories.

- Safety claims: “We interpreted it, therefore it’s safe” is not a logically valid leap.

- Trust: Real trust requires defensible decisions plus recourse—not just mechanistic insight.

If you want a governance framing, go through this Enterprise AI canon:

- The Enterprise AI Operating Model: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-operating-model/

- The Enterprise AI Runbook Crisis: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-runbook-crisis-model-churn-production-ai/

- Who Owns Enterprise AI? (Decision Rights): https://www.raktimsingh.com/who-owns-enterprise-ai-roles-accountability-decision-rights/

- The Intelligence Reuse Index: https://www.raktimsingh.com/intelligence-reuse-index-enterprise-ai-fabric/

Conclusion: interpretability needs a more mature promise

A key insight that’s also technically honest:

Mechanistic interpretability is shifting from “explain the whole model” to “extract enough causal structure to govern it.”

That is not retreat. It is maturity.

The frontier-era standard of intellectual honesty is this:

- Here is what we can explain.

- Here is what we can test causally.

- Here is what remains non-compressible or unstable.

- And here is how we govern the system anyway.

That is the future of responsible interpretability.

If this article changed how you think about AI interpretability, share it. The most dangerous AI myths are the ones that sound comforting.

Glossary

Mechanistic interpretability: Explaining model behavior by identifying internal computational mechanisms (circuits, features, causal pathways), not just input-output correlations. (arXiv)

Completeness problem: The possibility that not all model behaviors admit explanations that are simultaneously faithful, general, compact, and stable.

Superposition: A representational strategy where multiple features share the same internal space, creating interference and polysemantic units. (arXiv)

Polysemanticity: When a unit/feature participates in multiple unrelated concepts or behaviors. (arXiv)

Sparse autoencoders (SAEs): Methods used to extract sparse, interpretable features from dense activations, partially “unmixing” superposed representations. (Anthropic)

Non-robust features: Predictive cues that improve accuracy but are brittle and often misaligned with human perception or concepts. (arXiv)

Underspecification: When ML pipelines can return many different predictors with similar test performance but different real-world behavior. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

Causal abstraction: A framework for judging whether a higher-level explanation is a faithful simplification of a lower-level causal mechanism. (arXiv)

FAQ

1) Is this arguing mechanistic interpretability is pointless?

No. It argues that completeness is a risky promise. Interpretability can still deliver strong local mechanisms, causal tests, and practical safety benefits. (arXiv)

2) Why can’t we just scale interpretability tools until we explain everything?

Scaling helps, but structural issues like superposition and underspecification suggest the obstacle is not tooling alone; it’s how frontier models represent information and how many equivalent mechanisms can exist. (arXiv)

3) Do sparse autoencoders solve interpretability?

They are a major advance, especially for feature discovery at scale, but they do not guarantee uniqueness of explanation or that every behavior will become compactly human-interpretable. (Anthropic)

4) What is the best goal for interpretability in enterprises?

Move from “explain everything” to “extract enough causal structure to govern decisions”—then pair it with monitoring, runbooks, recourse mechanisms, and decision rights. (arXiv)

5) How should leaders use interpretability claims?

Treat them as evidence, not proof. Require intervention-based validation, define scope boundaries, and operationalize governance so safety does not depend on completeness.

References and further reading

- Elhage et al. Toy Models of Superposition (2022). (arXiv)

- Ilyas et al. Adversarial Examples Are Not Bugs, They Are Features (2019). (arXiv)

- D’Amour et al. Underspecification Presents Challenges for Credibility in Modern Machine Learning (JMLR, 2022; also arXiv 2020). (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

- Geiger et al. Causal Abstraction: A Theoretical Foundation for Mechanistic Interpretability (2023; updated arXiv versions). (arXiv)

Raktim Singh is an AI and deep-tech strategist, TEDx speaker, and author focused on helping enterprises navigate the next era of intelligent systems. With experience spanning AI, fintech, quantum computing, and digital transformation, he simplifies complex technology for leaders and builds frameworks that drive responsible, scalable adoption.