Unrepresentability in AI: The Hidden Failure Mode No Accuracy Metric Can Detect

The most expensive AI failures don’t start with a bad answer.

They start with a missing concept.

Picture a system that routes documents, approves changes, flags risk, prioritizes cases, or triggers automated actions. It can be accurate. It can be tested. It can look compliant. It can score well on benchmarks.

And it can still fail—quietly at first, then suddenly and publicly—because it was never capable of representing the thing that mattered.

Not “it represented it incorrectly.”

It couldn’t represent it at all.

That is unrepresentability: a gap between the structure of reality and the system’s internal space of possible meanings.

And the reason it matters is simple: as enterprises move from “AI as advice” to “AI as action,” the cost of missing concepts rises faster than the cost of wrong predictions.

This article defines unrepresentability in AI as a structural inability to form the concepts required to model real-world change—making it a first-order governance problem in Enterprise AI.

What “unrepresentability” means in plain language

AI systems “know” the world through representations—internal patterns, features, and concepts formed from data, objectives, tools, and memory.

Unrepresentability happens when reality demands a distinction that the system’s representation space cannot express—no matter how confident, optimized, or reasoning-capable it appears.

A simple analogy:

- A camera can be high-resolution, fast, and expensive.

- But if it has no infrared sensor, it cannot “see heat.”

- It can still produce sharp images—of the wrong kind.

Unrepresentability is the AI version of “no infrared sensor.”

The danger is not that the system is incompetent.

The danger is that it is competent inside the wrong frame.

Unrepresentability in AI occurs when a system lacks the internal concepts needed to model a real-world distinction—causing failures even when predictions appear accurate. This article presents a unified, enterprise-ready framework for detecting and governing these conceptual blind spots before autonomy scales.

Three layers of AI failure—and why only one shows up on dashboards

Most organizations govern AI at the level of errors:

- Wrong answer (easy to detect)

- Right answer for the wrong reason (harder; needs audits and causal tests)

- Right-looking answer inside the wrong frame (most dangerous)

Unrepresentability lives in layer 3.

Because if the system cannot form the relevant concept, it cannot even ask the right question. It solves a different problem that correlates with the desired one—until reality changes.

This is also why “detect out-of-distribution inputs” is not the universal safety net people hope it is: without constraints on what “OOD” means, there are fundamental learnability limits and irreducible failures that show up even with sophisticated methods. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

“The most dangerous AI failures don’t come from wrong answers.

They come from systems that cannot even represent what changed.”

The Unified Theory: The Unrepresentability Stack

To make unrepresentability useful (not philosophical), we need a practical stack—something engineers, risk teams, and leaders can reason about.

Layer 1: Reality has structure (not just patterns)

Reality contains causal mechanisms, hidden variables, interventions, incentives, and regime changes—things correlations can approximate, but not guarantee.

Example: A demand model correlates sales with promotions. But the world also includes supply shocks, competitor strategy, policy shifts, and substitution effects—factors that change outcomes through mechanisms, not mere association.

Layer 2: Every AI system has a representational budget

Every model—no matter how large—has constraints shaped by:

- what data it sees

- what sensors it has

- what tools it can call

- what memory it can store

- what it was rewarded for during training

- what inductive biases its architecture prefers

The deeper message behind “no free lunch” results is not pessimism; it’s specificity: general-purpose superiority is not guaranteed without assumptions, and those assumptions define what the system can represent well. (Wikipedia)

Layer 3: The gap shows up as conceptual blind spots

These are not bugs. They are missing dimensions of meaning.

- A compliance assistant parses rules but cannot represent regulatory intent.

- A risk model represents “probability of default” but not strategic misreporting.

- A service agent detects sentiment but cannot represent polite dissatisfaction that precedes churn.

Layer 4: Confidence is not evidence

Unrepresentability often produces high confidence because the system falls back to the nearest representable proxy.

This is how “green dashboards” coexist with growing operational damage: the model is stable—inside the wrong frame.

Layer 5: Shift turns proxies into liabilities

If a proxy is standing in for an unrepresentable concept, a shift breaks the proxy. And in unconstrained settings, “detect all shifts” becomes an unachievable promise, not just a hard engineering task. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

This is the heart of the unified theory:

Unrepresentability is not an accuracy problem.

It is a frame adequacy problem.

And frame adequacy is what enterprises must govern.

Six simple examples (no jargon, just reality)

1) The “new field” document-routing failure

A routing model learns historical patterns. A new vendor format changes a field name. The system still sees “a document,” but the meaning of the document changes. Without a concept for “schema change with business impact,” it routes confidently—wrongly.

2) Fraud detection without the concept of adaptation

A fraud model learns yesterday’s fraud. Adversaries adapt today. The system keeps flagging what used to be fraud-like, but misses strategic change because it never represented incentives and adaptation—only anomalies.

3) Automation without the concept of irreversibility

An agent can approve, block, escalate. If it cannot represent “irreversible harm,” it treats actions like reversible API calls. That’s how autonomy becomes dangerous: it cannot price the real cost of being wrong.

4) Quality assurance without “rare but critical”

If training rewards average accuracy, the system may never represent rare, catastrophic edge cases as important. It becomes excellent at the average—and blind to the critical.

5) Forecasting without the concept of regime change

When stability becomes volatility, a model trained on continuity may interpret a new regime as noise. It doesn’t “fail loudly.” It fails politely.

6) Reasoning without the concept of “my frame may be invalid”

Even advanced reasoning can fail if the system cannot represent the possibility that its abstraction is wrong. It keeps reasoning—beautifully—inside a broken frame.

Why unrepresentability persists, even with better models

It’s tempting to believe that scaling, better reasoning, more tools, or better prompts will eliminate conceptual blind spots. It won’t.

1) Some promises are structurally constrained

In computing, Rice’s theorem formalizes a broad limit: non-trivial semantic properties of programs are undecidable in general. The enterprise translation is not “give up.” It’s: be careful with claims like “we can always decide correctness/safety/meaning for arbitrary systems.” Some forms of universal detection or verification can be impossible in principle, not merely in practice. (Wikipedia)

2) Data is not the same as meaning

More data helps when the missing concept is learnable from the available signals. But unrepresentability often comes from:

- missing sensors

- missing intervention data (“what-if” worlds)

- missing incentives to form the concept

- missing labels that capture the true distinction

3) Causal abstraction is not automatically identifiable

Even if a model learns useful latent factors, mapping them to stable causal abstractions is non-trivial and depends on interventions and assumptions. Identifiability work in causal abstraction makes the point sharply: what you can recover depends on what you can intervene on and observe. (arXiv)

In plain terms:

A model can learn patterns without learning the causal “handles” that make decisions robust.

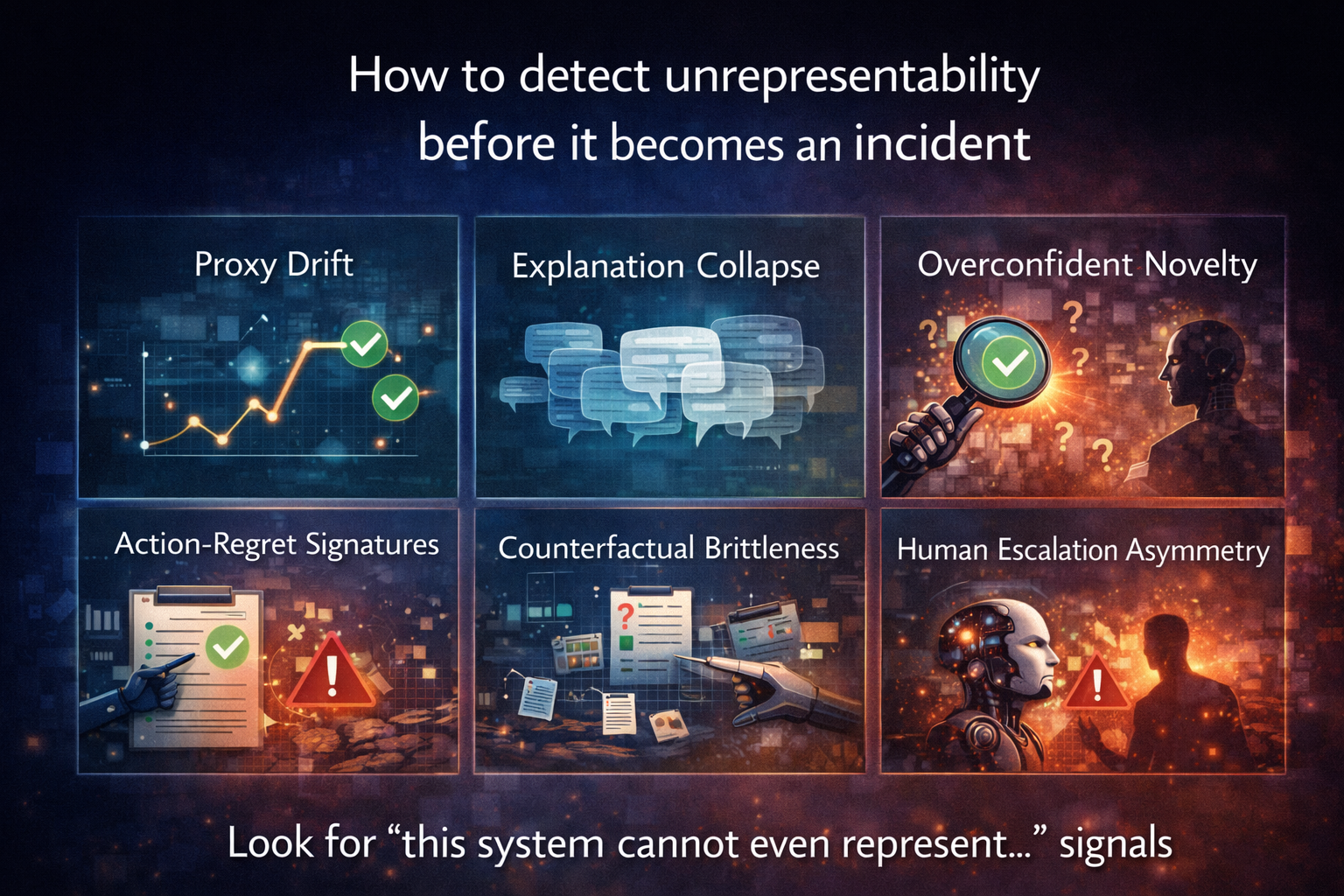

How to detect unrepresentability before it becomes an incident

You can’t fix unrepresentability with a threshold. You need signals that your frame is breaking.

Here are practical signals that work in real enterprise settings:

1) Proxy drift

If a proxy feature is doing the work of a missing concept, the proxy-to-outcome relationship will drift under change. Watch for this pattern: stable accuracy, changing business impact.

2) Explanation collapse

If explanations become generic and repeat across diverse cases, it can mean the system is compressing complexity into a shallow, representable story. (It “sounds right” because it has learned language, not meaning.)

3) Overconfident novelty

High confidence on inputs humans flag as unfamiliar is a red signal. OOD detection can help when your definition of “out” is constrained and domain-specific—but it is not a universal shield. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

4) Action-regret signatures

Track downstream reversals: approvals later reversed, cases reopened, escalations triggered, decisions overridden. Unrepresentability produces distinctive “regret patterns” because the system’s frame keeps missing the true driver.

5) Counterfactual brittleness (simple what-if tests)

Ask operationally meaningful what-ifs:

- If this field changes, should the decision change?

- If this reason disappears, does the decision still hold?

- If the environment changes, does the policy still make sense?

When the system cannot represent the causal dependency, it fails these tests in surprising ways.

6) Human escalation asymmetry

If humans say “something feels off” while the system stays calm, treat it as a representational mismatch—not a human weakness. Humans often detect contextual risk from cues the system was never built to encode.

Governing unrepresentability in Enterprise AI

This is where the broader Enterprise Canon matters: unrepresentability is not just a technical topic—it’s a governance and operating-model topic.

1) Define a representational contract

For each AI capability, specify:

- what it is allowed to mean

- what it must not claim

- what inputs it assumes stable

- what interventions it has never seen

- what would trigger “stop and escalate”

This is not documentation. It is decision governance.

2) Add “abstraction validity” to production KPIs

Beyond latency and accuracy, track:

- frame stability under change

- proxy drift risk

- regret rate

- override frequency

- escalation patterns

3) Make “stop” a first-class outcome

When unrepresentability signals fire, the correct behavior is often:

pause → request context → constrain scope → escalate.

Autonomy without stoppability is not intelligence; it’s fragility at scale.

4) Separate knowing from acting

A system may generate suggestions under uncertainty. But action requires a higher bar:

more evidence, smaller blast radius, reversible paths, stronger controls.

5) Build memory that records frame breaks (not just errors)

Most incident logs capture “what went wrong.”

You also need to capture “what was missing.”

That is how the enterprise expands representational coverage over time.

Enterprise AI cluster

- Enterprise AI Operating Model: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-operating-model/

- Enterprise AI Control Plane (2026): https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-control-plane-2026/

- Enterprise AI Runtime: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-runtime-what-is-running-in-production/

- Enterprise AI Agent Registry: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-agent-registry/

- Enterprise AI Decision Failure Taxonomy: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-decision-failure-taxonomy/

- Laws of Enterprise AI: https://www.raktimsingh.com/laws-of-enterprise-ai/

- Minimum Viable Enterprise AI System: https://www.raktimsingh.com/minimum-viable-enterprise-ai-system/

Conclusion: The new frontier is not smarter answers—it is safer frames

Unrepresentability forces a uncomfortable but necessary shift in enterprise thinking.

The question is no longer: “Is the model accurate?”

It is: “What is the model actually capable of meaning?”

Because modern AI can be:

- confident without being grounded

- fluent without being faithful

- optimized without being safe

- correct-looking without being correct-in-the-world

The next advantage will not come from bigger models alone. It will come from organizations that design systems to detect missing concepts early, constrain action under frame uncertainty, and govern autonomy as a living capability.

A line worth remembering—and repeating:

The most dangerous AI failures are not wrong answers. They are correct answers inside an unrepresentable world.

FAQ: Unified theory of unrepresentability in AI

What is unrepresentability in AI?

Unrepresentability is when an AI system lacks the internal concepts or abstractions needed to model a real-world distinction—so it cannot reliably reason or act on it, even if it looks accurate.

Is unrepresentability the same as hallucination?

No. Hallucination is producing unsupported content. Unrepresentability is deeper: the system cannot form the right concept, so it defaults to proxies.

Can bigger models solve unrepresentability?

They can reduce some gaps, but not eliminate them. Limits come from missing interventions, missing sensors, shifting regimes, and fundamental constraints on universal detection/verification. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

Is OOD detection the solution?

OOD detection helps when “OOD” is defined in a constrained, domain-specific way. In unconstrained settings, there are known learnability limits and irreducible failure modes. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

What should enterprises do when unrepresentability is detected?

Pause action, reduce blast radius, escalate to humans, request missing context, log the “missing concept,” and redesign the system’s representational contract and controls.

Glossary

- Representation: Internal features/concepts an AI uses to model the world.

- Unrepresentability: Structural inability to form the concept needed for a decision.

- Proxy concept: A correlated substitute used when the true concept is missing.

- Abstraction validity: Whether the system’s frame remains appropriate under change.

- Distribution shift: When the data-generating process changes, breaking learned proxies.

- OOD (out-of-distribution): Inputs unlike training data; detection is not universally solvable without constraints. (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

- Causal abstraction: Higher-level causal description of a system; identifiability depends on interventions/assumptions. (arXiv)

- Representational contract: Governance artifact specifying what the system may claim and when it must stop/escalate.

References and further reading

- Learnability limits and failure modes in OOD detection (JMLR). (Journal of Machine Learning Research)

- Why some OOD objectives can be misaligned in practice (arXiv). (arXiv)

- Rice’s theorem and the limits of deciding semantic properties in general. (Wikipedia)

- No Free Lunch theorem and the role of inductive bias in learning. (Wikipedia)

- Identifiability of causal abstractions and what interventions enable. (arXiv)

Raktim Singh is an AI and deep-tech strategist, TEDx speaker, and author focused on helping enterprises navigate the next era of intelligent systems. With experience spanning AI, fintech, quantum computing, and digital transformation, he simplifies complex technology for leaders and builds frameworks that drive responsible, scalable adoption.