Formal Theory of Delegated Authority in Enterprise AI

As enterprises deploy AI systems that can recommend, decide, and increasingly act in the real world, a quiet but dangerous mismatch is emerging.

Execution has become automated, fast, and cheap—while accountability remains slow, human, and institutionally anchored. When an AI agent triggers a transaction, modifies a system, or affects a customer outcome, logs can tell us what executed the action, but they rarely tell us who had the authority to cause it.

This gap is not a technical detail; it is the central reason agentic AI struggles to scale safely in enterprises.

This article introduces a formal theory of delegated authority for Enterprise AI, arguing that true accountability must follow authority flow, not execution flow—and showing how organizations can operationalize this principle to govern autonomous systems without slowing innovation.

Human oversight in AI systems

Enterprises have always delegated work.

A leader delegates to a team. A team delegates to a process. A process delegates to a system.

AI changes a single variable—but it changes everything: execution becomes cheap and fast, while responsibility stays slow, social, and human.

That gap creates a new class of institutional failures—ones that don’t show up in accuracy charts or model evals.

When an AI agent takes an action, the logs tell us what executed it.

But they often cannot tell us whose authority made it legitimate.

This is not a “governance nuance.” It is the core reason agentic AI struggles to scale safely inside real enterprises: accountability is being attached to the wrong object.

This article proposes a practical formal theory of delegated authority for Enterprise AI—“formal” in the sense that it defines objects, flows, constraints, and invariants clearly enough to implement, audit, and defend. No math. No legal theatre. A clean operational model you can ship.

It centers on one rule.

The prime rule

Accountability must follow authority flow, not execution flow.

- Execution answers: Which system did it?

- Authority answers: Who had the right to cause it?

If you only capture execution, you will fail the questions auditors, regulators, customers, and your own board ask after the first serious incident.

Why this matters now (and why the world is converging on it)

Across the globe, governance frameworks are converging on the same theme: clear roles, responsibilities, and human oversight with real authority—not ceremonial review.

- NIST AI RMF 1.0 frames “GOVERN” as a core function across the AI lifecycle—focused on organizational processes for oversight, accountability, and risk management. (NIST Publications)

- ISO/IEC 42001 establishes an AI management system approach, pushing organizations to define responsibilities and manage AI risks across the lifecycle. (ISO)

- The EU AI Act places explicit obligations on deployers of high-risk AI systems—including assigning human oversight to persons with the necessary competence and authority, plus monitoring and log retention obligations. (AI Act Service Desk)

In other words, the question has shifted:

It’s not “Do you have AI?”

It’s “Who is accountable—and do they actually have authority?”

A simple example that exposes the problem

Imagine a procurement agent that can:

- read vendor quotes

- create purchase orders

- schedule payments

One day, it creates a purchase order that violates policy (wrong vendor tier, missing approvals, budget exceeded).

Your logs show:

- Executed by: ProcurementAgent-v3

- API call: create_PO

- Time: 10:14:03

That’s execution flow.

But the real questions are authority questions:

- Who authorized this agent to spend up to this amount?

- Was it acting on behalf of a specific budget owner?

- Was the delegation conditional (vendor class, geography, exception rules)?

- Did the agent escalate when conditions weren’t met?

- Who was the designated overseer with the power to pause or revoke?

If you can’t answer these precisely, you don’t have governance. You have a narrative.

The key distinction: execution flow vs authority flow

Execution flow = “what happened”

- tool calls

- system responses

- retries

- outputs

Authority flow = “why it was permitted”

- a valid delegation exists

- scope is explicit

- constraints are satisfied

- oversight is armed and interruptible

- evidence binds authority to action

Authority flow must remain auditable independent of the model.

Models change. Prompts change. Policies change. Teams change. But accountability cannot be allowed to drift.

This lifecycle accountability emphasis is exactly why AI governance standards and frameworks treat governance as a continuous function—not a one-time certification. (NIST Publications)

The Delegated Authority Stack

The minimum objects you need for accountable autonomy

A formal theory needs objects. These are the minimum objects required for delegated authority to be real—not rhetorical.

1) Principal (the authority holder)

A role (or person) that legitimately owns decision rights: budget owner, operations controller, risk officer, service owner.

Key point: In enterprise AI, “principal” is often a role, not a single human.

2) Delegate (the agent or sub-system)

An AI agent, workflow, tool, or subordinate system that can act.

3) Scope (what is allowed)

The action types and resources the delegate may touch, for example:

- “Create PO” but not “Release payment”

- “Issue refund” but only within defined limits

- “Modify configuration” but only in sandbox

Scope is the difference between assistance and authority.

4) Constraints (when it is allowed)

Rules that must hold at the moment of action:

- approvals, thresholds, time windows

- separation-of-duties constraints

- policy checks (vendor tier, customer status, risk flags)

- escalation triggers (“ask a human when the case is ambiguous”)

You can define constraints without numbers. What matters is that they’re enforceable.

5) Attribution (the “on-behalf-of” claim)

The delegate must be able to prove:

“I acted on behalf of this principal under this scope and these constraints.”

This is where many enterprises fail today: agents are deployed like service accounts with broad access, not as delegates with bounded authority.

A growing technical literature is converging on this idea: authenticated, authorized, and auditable delegation for AI agents—often building on existing web identity and authorization infrastructure (e.g., OAuth/OpenID-style patterns) so delegation is scoping-compatible and auditable. (arXiv)

6) Oversight (who can intervene)

Not “someone can watch a dashboard.”

Oversight means a named role with real powers:

- pause/deny actions

- narrow scope

- revoke delegation

- require escalation paths and evidence

This aligns directly with the EU AI Act’s language that deployers must assign human oversight to persons with the necessary competence, training, and authority. (AI Act Service Desk)

7) Evidence (the decision record)

A decision record is not just logs. It’s the minimum proof bundle:

- delegation chain

- scope and constraints at time of action

- policy checks and outcomes

- escalation/override events

- final action and side effects

This is Decision Integrity made operational.

If you want to get canonical view of this, go to:

- The Enterprise AI Operating Model (pillar): https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-operating-model/

- Control Plane: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-control-plane-2026/

- Runtime: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-runtime-what-is-running-in-production/

- Agent Registry: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-agent-registry/

- Decision Failure Taxonomy: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-decision-failure-taxonomy/

- Laws of Enterprise AI: https://www.raktimsingh.com/laws-of-enterprise-ai/

The Four Invariants

Non-negotiables for delegated authority

If you only remember four statements, remember these.

Invariant 1: No action without a principal

If you cannot name the authority holder, the action is unauthorized—no matter how correct the agent’s reasoning was.

Invariant 2: Delegation must be explicit and scoped

“Agent has access” is not delegation. Delegation requires explicit scope + constraints.

Invariant 3: Oversight must be interruptible

Oversight that cannot stop the action is theatre.

Invariant 4: Evidence must bind authority to action

Every material action must be provably tied to:

- who delegated

- what scope

- under what constraints

- with what oversight

This is what turns accountability from slideware into an operational control surface.

Simple enterprise examples

Example 1: Customer refund agent

Good delegation

- Can propose refunds always

- Can execute refunds only within defined limits

- Must escalate when the case triggers policy flags

- Must attach evidence of the “on-behalf-of” approval chain

Bad delegation

- Refund agent has broad payment access

- Logs show it issued a refund

- Nobody can explain whose authority covered that refund

Example 2: IT operations patching agent

Good delegation

- May patch low-risk systems in maintenance windows

- Must open a change record for high-risk systems

- Must obtain explicit on-call approval before production rollout

- Must be stoppable mid-flight by the service owner

Example 3: Contract drafting agent

Good delegation

- May draft clauses and redlines

- May not send externally

- Must route to legal principal for approval

- Must retain evidence of policy constraints it checked

In all three: execution is easy; authority is the real product.

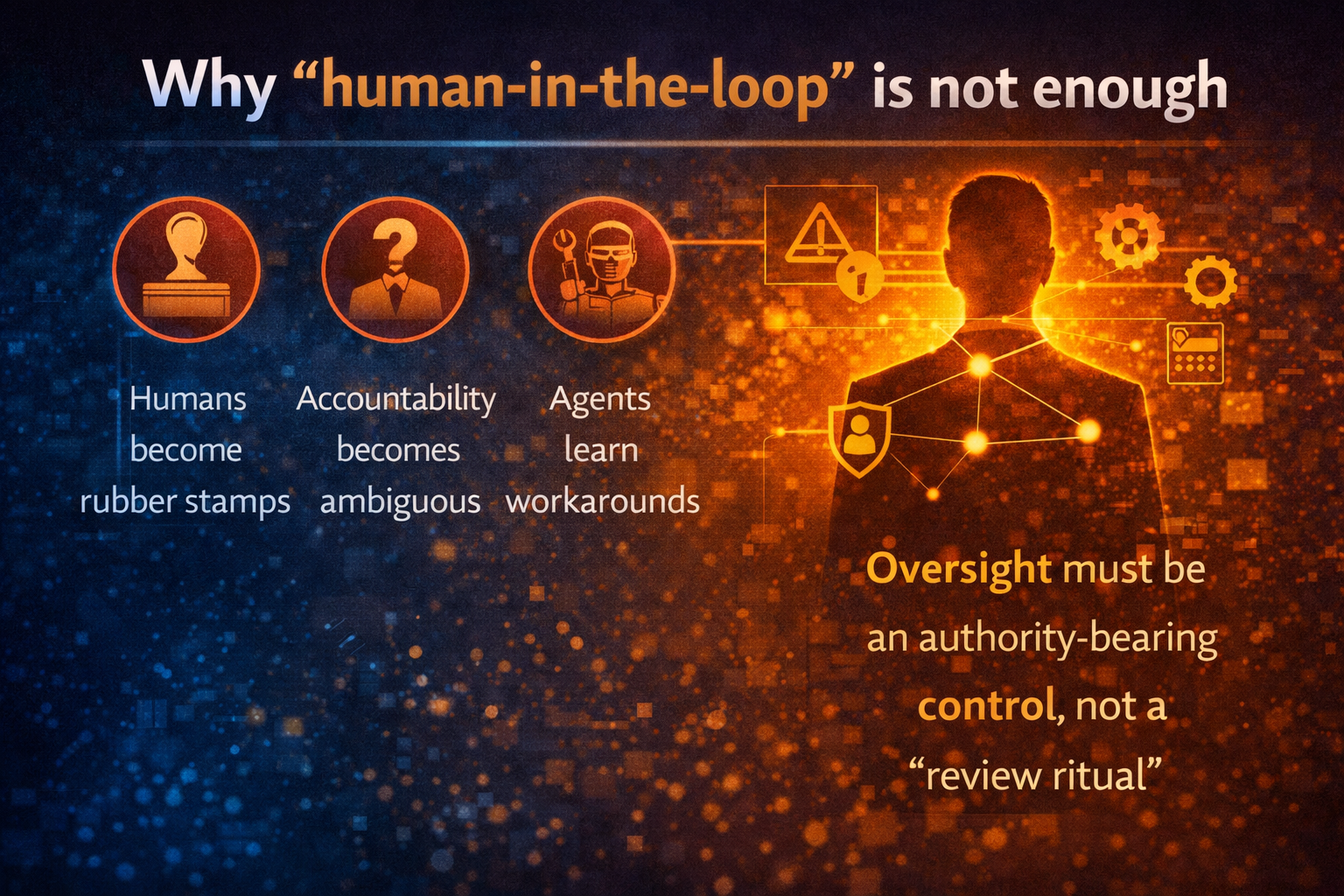

Why “human-in-the-loop” is not enough

Why “human-in-the-loop” is not enough

Many organizations assume: “We’ll keep a human in the loop, so we’re safe.”

But human-in-the-loop without delegated authority design becomes a trap:

- humans become rubber stamps

- accountability becomes ambiguous

- agents learn workarounds

- escalations become noisy and ignored

- risk silently moves from the model to the institution

The EU AI Act framing is not merely “a human exists.” It is oversight by people with competence and authority—a crucial difference that most deployments currently miss. (AI Act Service Desk)

Practical translation:

Oversight must be an authority-bearing control, not a “review ritual.”

The Delegation Contract

What to implement

To operationalize this theory, enterprises need a Delegation Contract per agent and per action class.

A Delegation Contract should specify:

- Principal role (who owns the decision right)

- Delegate identity (which agent, which version, which runtime)

- Scope (allowed actions/resources)

- Constraints (policies, thresholds, time windows, separation-of-duties)

- Escalation policy (when to ask, who to ask, what evidence is required)

- Override and revocation (how to stop, who can stop, what happens mid-flight)

- Evidence requirements (what must be recorded to prove authority flow)

This maps naturally onto your Enterprise AI Control Plane framing: a layer that governs action boundaries, permissions, policy checks, and logging—independent of model internals.

The Authority Graph

Why RACI charts fail in the age of agents

In real enterprises, authority is not a straight line. It is a graph:

- budget authority

- risk authority

- operational authority

- data authority

- customer-impact authority

Agents cross these domains quickly—often within a single workflow.

So you need an Authority Graph that can answer:

- Which authority domains does this action touch?

- Are we allowed to compose them in one step?

- Where must we insert a checkpoint?

- Who is the principal of record for each domain?

Traditional RACI charts describe “who is responsible” socially.

They do not define delegable, machine-enforceable authority operationally.

“On-behalf-of” access

The missing technical primitive for accountability

A working delegated authority system needs “on-behalf-of” semantics:

- the agent has its own identity

- the principal has an identity/role

- the action is taken by the agent acting for the principal

- credentials and the evidence ledger bind them

Modern identity and security thinking for agents is moving in exactly this direction: allow delegation that is authenticated, scoped, and auditable—while staying compatible with widely deployed authorization infrastructure. (arXiv)

This is not “just security.”

It is accountability plumbing.

Failure modes (how delegated authority breaks in production)

1) Silent scope creep

Agent starts “draft-only,” later gains execution ability without upgrading controls.

2) Shadow principals

No clear decision-right owner, so escalation goes nowhere.

3) Evidence without meaning

Logs exist, but cannot prove a legitimate authority chain existed at the time of action.

4) Oversight fatigue

Too many escalations, not enough structured thresholds → humans stop paying attention.

5) Liability inversion

The maintainer gets blamed, while the authority holder claims they never delegated.

A formal theory is valuable because it makes these failures predictable—and therefore preventable.

Enterprise AI canon

In canon language:

- Control Plane enforces delegation contracts, scopes, constraints, revocation

- Runtime executes tool calls, retries, state changes, monitoring

- Agent Registry stores identity, capabilities, and allowed scopes

- Decision Integrity binds authority → decision → action via evidence bundles

- Decision Failure Taxonomy classifies failures (scope breach, oversight failure, evidence gap)

- Pillar: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-operating-model/

- Control Plane: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-control-plane-2026/

- Runtime: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-runtime-what-is-running-in-production/

- Agent Registry: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-agent-registry/

- Decision Failure Taxonomy: https://www.raktimsingh.com/enterprise-ai-decision-failure-taxonomy/

- Laws: https://www.raktimsingh.com/laws-of-enterprise-ai/

Practical checklist (implementation-ready, not jargon)

- Name a principal for every action domain

- Create delegation contracts per agent + action class

- Enforce scoped permissions with on-behalf-of attribution

- Ensure oversight is interruptible and revocable

- Record evidence bundles that bind authority → action

- Monitor scope creep and policy drift as first-class risks

- Align governance lifecycle to NIST AI RMF and ISO/IEC 42001 principles (NIST Publications)

- For high-risk deployments, map controls to deployer obligations and oversight expectations (AI Act Service Desk)

Conclusion:

The real promise of delegated authority

Most AI governance tries to make models safer.

A formal theory of delegated authority does something more fundamental:

It makes autonomy accountable.

Because in enterprises, the question is never “Did the system act?”

It is always: “Who had the right to cause that action—and can you prove it?”

When accountability follows authority flow, agentic AI stops being a risk you tolerate.

It becomes an operating model you can scale.

The future of enterprise AI will not be decided by how well models reason—but by how clearly authority is delegated, constrained, and proven.

When accountability follows authority flow instead of execution flow, agentic AI becomes not just powerful—but governable, auditable, and scalable.

Glossary

- Principal: The role/person that legitimately owns the decision right.

- Delegate: The agent/subsystem acting under delegated authority.

- Scope: The set of allowed actions/resources.

- Constraints: Conditions that must be satisfied at time of action.

- Oversight: A role with real intervention powers (pause, deny, revoke).

- Evidence bundle: The minimum proof packet binding authority to action.

- Authority graph: The multi-domain network showing how authority is distributed and composed.

- Delegated authority (AI): A bounded, auditable right granted by a human or organizational principal to an AI system to act under explicit scope, constraints, oversight, and revocation.

-

Authority flow: The chain of delegation, constraints, and oversight that makes an AI action legitimate—independent of the system that executed it.

Execution flow: The technical sequence of actions, tool calls, and outputs showing what an AI system did, but not why it was permitted.

Delegated authority (AI): A bounded right granted by a principal to an agent to perform specific actions under explicit scope, constraints, oversight, and audit evidence. (ISO)

- On-behalf-of action: An action performed by an agent while cryptographically/auditably attributable to a principal’s delegated scope. (arXiv)

- Human oversight with authority: Oversight performed by persons empowered to intervene, stop, or revoke actions—explicitly reflected in deployer obligations for high-risk AI contexts. (AI Act Service Desk)

FAQ

What is delegated authority in AI agents?

Delegated authority is when a principal grants an AI agent permission to take specific actions under explicit scope, constraints, oversight, and audit evidence—so accountability remains clear across the lifecycle. (ISO)

What’s the difference between authority flow and execution flow?

Execution flow shows what the agent did (calls, logs). Authority flow shows why it was allowed (delegation, scope, constraints, oversight, evidence).

Why aren’t audit logs enough?

Logs prove execution, not legitimacy. Without delegation chains, scope/constraint records, and oversight events, you can’t prove the action was authorized.

How does the EU AI Act relate to this?

For high-risk AI systems, deployers must assign human oversight to persons with competence, training, and authority, and must monitor and retain logs—reinforcing that accountability needs enforceable oversight and evidence. (AI Act Service Desk)

How does ISO/IEC 42001 help?

ISO/IEC 42001 provides a management-system lens for AI governance across the lifecycle—useful scaffolding for responsibility assignment, risk controls, oversight, and continuous improvement. (ISO)

Why is execution flow not enough for AI accountability?

Execution flow shows what happened, not who had the right to make it happen. Without authority flow, organizations cannot reliably assign responsibility, liability, or governance after AI incidents.

How does delegated authority relate to the EU AI Act?

The EU AI Act emphasizes human oversight by persons with competence and authority. Delegated authority provides the operational model that makes this requirement enforceable in production systems.

Is human-in-the-loop sufficient for AI governance?

No. Human-in-the-loop without authority design leads to rubber-stamping and ambiguous accountability. Oversight must include the power to interrupt, revoke, and constrain actions.

How does this fit into enterprise AI architecture?

Delegated authority is enforced through the Enterprise AI Control Plane, supported by agent registries, decision ledgers, and runtime enforcement mechanisms.

References

- NIST, AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0). (NIST Publications)

- ISO, ISO/IEC 42001:2023 Artificial intelligence — Management system. (ISO)

- EU AI Act (official service desk), Article 26: Obligations of deployers of high-risk AI systems. (AI Act Service Desk)

- South et al., Authenticated Delegation and Authorized AI Agents (arXiv, 2025). (arXiv)

- “A Secure Delegation Protocol for Autonomous AI Agents” (arXiv, 2025). (arXiv)

Further reading

- NIST overview page for AI RMF and supporting resources. (NIST)

- EU AI Act high-risk system obligations context (Chapter III). (Artificial Intelligence Act)

Raktim Singh is an AI and deep-tech strategist, TEDx speaker, and author focused on helping enterprises navigate the next era of intelligent systems. With experience spanning AI, fintech, quantum computing, and digital transformation, he simplifies complex technology for leaders and builds frameworks that drive responsible, scalable adoption.